Security contexts can also be analyzed based on the regional variable. In this regard, there are at least three dimensions to consider in the case of South Sudan.

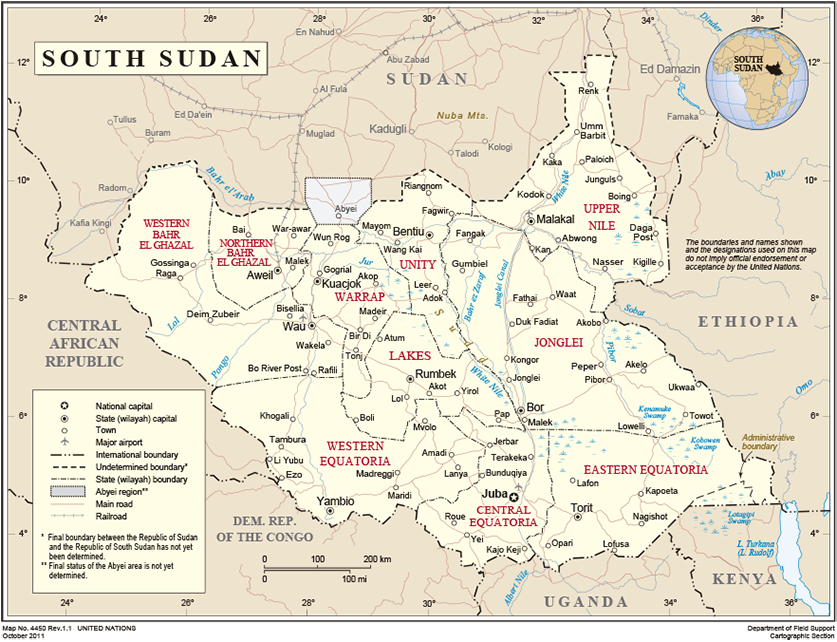

Source: United Nations

The evolution of the political and administrative structure of governance in South Sudan can be mapped through key periods:

Since the arrival of Turco-Egyptian regime (1821 – 1881) and before the independence in 1956, South Sudan had not been at peace except during the post-pacification period (1930-1954) of the Anglo-Egyptian rule. This regime was resisted by many ethnic groups in South Sudan and that contributed later on to the adoption of various ordinances, which culminated with the “Southern Sudan Policy” in 1930. As early as 1921 and before the formulation of Southern Sudan Policy, the system of government in southern Sudan had been based on the principles of native administration.

This decentralized system of governance contributed not only to maintaining peace and stability, but also to restoring and protecting the systems and institutions of traditional authorities in South Sudan. The policy administratively separated the north from the south, and while the north benefited more from development initiatives, the south remained underdeveloped. In practice, the outcomes of this policy’s implementation during the colonial period had lasting effects, particularly in terms of claims and grievances between regions.

This decentralized system of governance contributed not only to maintaining peace and stability, but also to restoring and protecting the systems and institutions of traditional authorities in South Sudan. The policy administratively separated the north from the south, and while the north benefited more from development initiatives, the south remained underdeveloped. In practice, the outcomes of this policy’s implementation during the colonial period had lasting effects, particularly in terms of claims and grievances between regions.

In addition to its reliance on native administration, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan was divided into eight provinces, which were initially ambiguous when established in 1929 but became more clearly defined by the time of World War II. The provinces corresponding to present-day South Sudan were three: Equatoria, Upper Nile, and Bahr al Ghazal.

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan provinces. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Post-independence Sudanese rulers consistently focused on dismantling the Southern Sudan Policy, which was based on a traditional system of governance, and sought to replace it with a policy of Arabization and Islamization in Southern Sudan. In addition, the civil war in Sudan (1955–1972 and 1983–2005) caused enormous disruption. Although the system of governance remained largely unitary since independence in 1956, the approach alternated between decentralization and deconcentration. Each province delegated powers to local government units, known as rural councils in rural areas and municipal or town councils in urban areas. These councils were simply administrative units of provinces exercising deconcentrated and delegated powers to maintain law and collect revenue on behalf of the provincial authorities. From 1973, a complicated series of administrative divisions led to a new structure of 18 regions (mudiryas) in 1976 with Lakes province split from Bahr al Ghazal province, Jonglei split off from Upper Nile and Equatoria divided into East and West Equatoria.

With the conclusion of Addis Ababa Peace Agreement in 1972 that granted Southern Sudan regional autonomy, the regional government exercised legislative and executive authority without judicial authority and with system of decentralized local government. This decentralized local government continued with 24 local government councils until 1975 and then divided into 48 area councils in 1981.

With the conclusion of Addis Ababa Peace Agreement in 1972 that granted Southern Sudan regional autonomy, the regional government exercised legislative and executive authority without judicial authority and with system of decentralized local government. This decentralized local government continued with 24 local government councils until 1975 and then divided into 48 area councils in 1981.

Following the abrogation of the Addis Ababa Peace Agreement and the outbreak of the second civil war in 1983, two authorities — the Government of Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) — governed Southern Sudan until the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2005. During the early years of the liberation struggle in the 1980s, the SPLM relied heavily on traditional authorities to govern the areas under its control. As more territory and civilian populations came under SPLM control, a National Convention was convened in 1994, during which it was resolved to recognize the three regions of Southern Sudan (the former provinces of Bahr el Ghazal, Equatoria, and Upper Nile) and to establish a civil administration based on a decentralized system of government.

In 1991, the Islamic Regime of the former president Bashir that took power in 1989 adopted an Islamic federal structure of nine provinces (willaya) corresponding to the 9 former provinces. The number of provinces was then increased to 26 in 1994, with ten of them in Southern Sudan.

The 2005 Sudan Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) between the Islamic-led Government of Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) ended the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005) and established a framework for a new administrative system. It also granted the people of Southern Sudan the right to self-determination, allowing them to decide whether to remain part of a united Sudan or to form their own independent state. The CPA provided Southern Sudan with a regional autonomous government, complete with its own constitution, parliament, financial resources (both oil and non-oil), regional army and security forces, and judiciary.

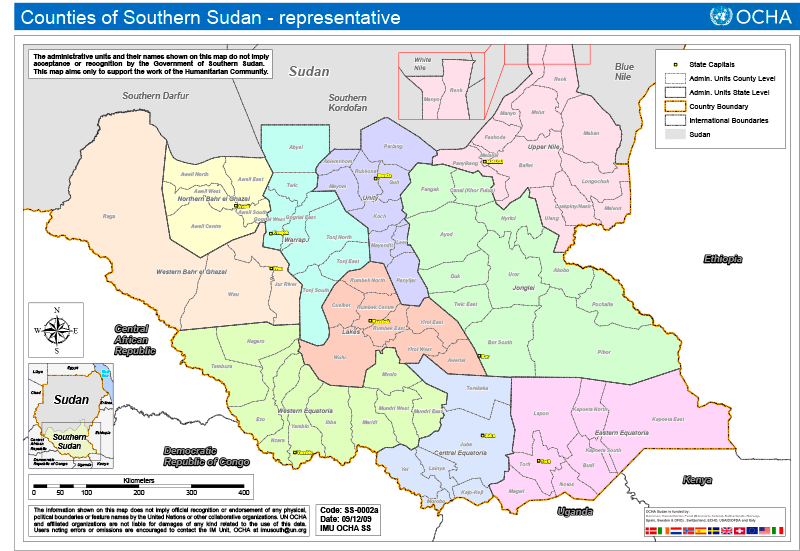

In particular, the 2005 Interim Constitution of Southern Sudan (ICSS) laid a strong constitutional foundation for the separation of powers, checks and balances, and a political-administrative system based on a presidential model of governance and a decentralized federal structure. During the CPA’s transitional period (2005–2011), Southern Sudan adopted a system of decentralized territorial federalism at the state level and implicitly adopted ethnic federalism at the local government level.

Counties of Southern Sudan. Source: OCHA.

The system of government to be adopted after the conduct of the referendum on self-determination was guaranteed in the 2005. Specifically, Article 208 (7) made it clear that if the outcome of the referendum on self-determination favors secession, the constitution would remain in force for an independent Southern Sudan.

The system of government to be adopted following the referendum on self-determination was guaranteed in the 2005 Interim Constitution of Southern Sudan (ICSS). Specifically, Article 208 (7) stated clearly that if the outcome of the referendum favored secession, the constitution would remain in force for an independent Southern Sudan.

Contrary to these provisions, the Transitional Constitution of the independent South Sudan, 2011 (TCSS, 2011) adopted instead a centralized and semi federal system.

Regarding the administrative structure of governance, although the ten states were retained in post-independence South Sudan, the issue of federalism emerged during negotiations of the 2015 Peace Agreement. The opposition rebel movement, the SPLM-In-Opposition (SPLM-IO), demanded the adoption of a federal system, while the SPLM-led government resisted this demand. Ultimately, the call for federalism was acknowledged only in the preamble of the 2015 Peace Agreement—rather than as a standalone provision. This agreement, which ended the first civil war (2013–2015), maintained the ten-state structure.

Immediately after the signing of the 2015 Peace Agreement in August, the President of South Sudan unilaterally issued a decree in October 2015 establishing 28 states to replace the 10 states recognized in the Peace Agreement. This decision was largely influenced by the Jieng (Dinka) Council of Elders (JCE), a self-appointed tribal advisory body that invoked the name of the Dinka ethnic group to advance its political interests and exert influence over the President’s decisions. The creation of the 28 states was largely delineated along ethnic lines.

28 States of South Sudan. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The national legislature approved the constitutional amendment in November 2015. With the eruption of the Second South Sudan Civil War (2016 – 2018) and before the signing of the 2018 Peace Agreement, the President issued another decree in January 2017 of further subdivision of the country from 28 into 32 states.

South Sudan is located in the East African region. It shares borders with Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and the Central African Republic.

Source: United Nations

Of South Sudan’s six neighboring countries, four—Sudan, Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and the Central African Republic—are experiencing internal conflicts. The remaining two, Kenya and Uganda, are facing political unrest and waves of public protests. Its proximity to the Horn of Africa presents South Sudan with unique geopolitical challenges and dynamics. Four interrelated pressures—violent conflict, political instability, economic hardship, and environmental degradation—shape these region’s dynamics, with far-reaching consequences for South Sudan.

Mongolian peacekeepers recently went on a long, multi-day patrol through the counties of Abiemnom and Mayom in northern South Sudan to assess the security situation.

Photgraphy: Peter Bateman/UNMISS

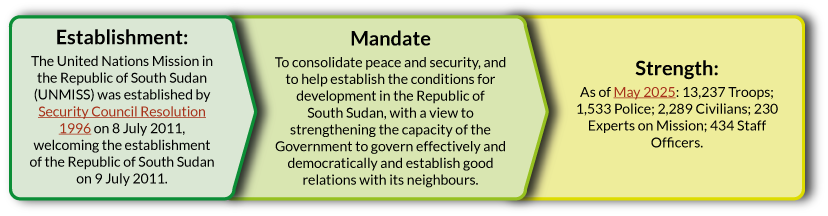

Following more than two decades of civil war, the Government of the Sudan and Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) signed the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement. This paved the way for an interim period, referendum and independence for South Sudan on July 9, 2011. The United Nations Mission in the Sudan (UNMIS) was established by the UN Security Council under Resolution 1590 of 24 March 2005, in response to the signing of the CPA. UNMIS tasks were to support the implementation of the CPA, to perform certain functions relating to humanitarian assistance, protection, promotion of human rights, and to support African Union Mission in Sudan. By then, the United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) had been present for six years throughout southern Sudan and in the “three areas”, covering the contested Abyei Area and the northern Sudanese states of South Kordofan and Blue Nile. With the secession of South Sudan from Sudan on 9 July 2011, the mandate of UNMIS ended on 9 July 2011 with the UNSC officially ended the mission on 11 July 2011. The United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) deployed in UNMIS’ place in South Sudan. In early July 2011, the United Nations Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA) had also deployed to oversee a ceasefire in the Abyei Area, while UNMIS rapidly drew down on expiration of its mandate.